Discussion summary

Janis Rotman Roundtable on Food Insecurity

With nearly one in five Canadians reporting that they’re unable to access adequate food, most often because they can’t afford it, food insecurity is among today’s most urgent social issues. Just weeks after Toronto declared food insecurity a public health emergency, the University of Toronto’s Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work brought together a group of the city’s leading experts on the subject to explore the problem, discuss solutions, and provide insight into the role that social work practitioners, policy makers, researchers and educators can play in addressing the problem.

The first annual Janis Rotman Roundtable on February 10 touched on a wide range of topics where there was mostly consensus, and occasionally lively debate. More than 20 individuals took part in the two-hour conversation, including researchers, frontline social workers, and executives from non-profit food and community service organizations.

“Our goal is to build connections, share knowledge and spark groundbreaking ideas that can influence classrooms, policy spaces, and ultimately the health and wellbeing of individuals, families and communities,” said Dean Charmaine Williams in launching the event.

These were some of the key themes in the discussion:

The face of food insecurity

The roundtable frequently cited the disproportionate impact of food insecurity on groups that have been marginalized. Participants shared firsthand accounts of young people, racialized people, Indigenous populations, immigrants and refugees, individuals with mental health issues and people with HIV — among others – struggling to access sufficient food. These accounts highlighted how intersecting identities and stigmas compound to create multiple barriers — to secure employment, stable housing, and other necessities — that further create vulnerability to poverty and food insecurity.

The participants also called attention to the persistent societal stigma attached to poverty and food insecurity. Contributors agreed that reducing this stigma, drawing on evidence-based methods developed by researchers from social work and other disciplines, is essential to efforts aimed at increasing society’s commitment to tackling the crisis.

The role of food banks

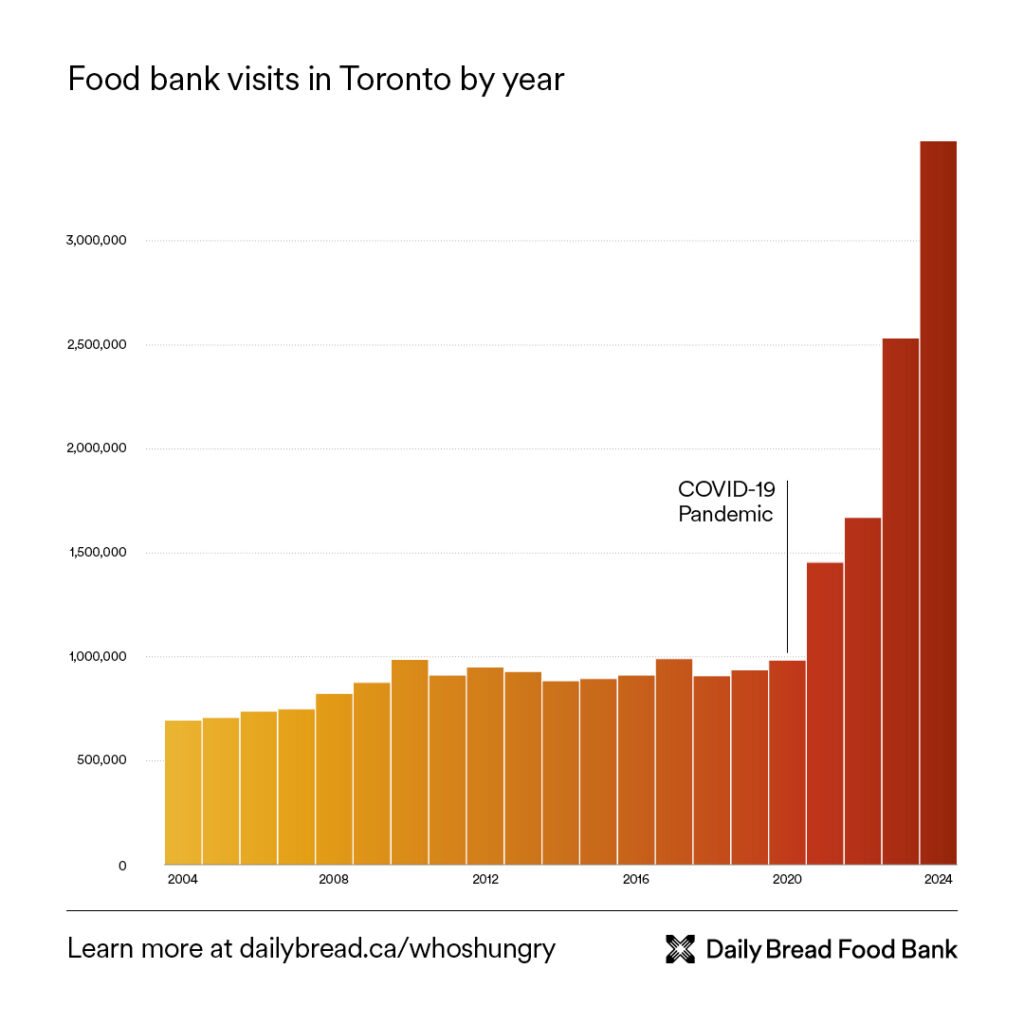

Participants expressed concern and frustration about the dramatic rise in food bank usage in recent years, with one in 10 Torontonians now relying on the service. The roundtable emphasized that food banks should be viewed as a temporary emergency measure, not a sustainable long-term solution to poverty and food insecurity. Yet several participants reminded the roundtable that, while substantive policy change to eradicate poverty is the goal, until that happens, some type of ongoing food provisioning is vital. As an example, they cited the necessity of providing food programs for children, whose development is so dependent on adequate nutrition.

There was accord on the critical role that food bank executives must play in advocating for measures that address the root causes of food insecurity, including income supports, affordable housing and stable employment. The roundtable agreed that food banks’ current messaging to the public — donate, but also advocate for change that will eliminate the need for food banks altogether — must continue and grow even stronger.

The public case for food security

A substantial portion of the conversation focused on how to mobilize the general public around food insecurity, with the larger objective of making it a key provincial and federal election issue. Participants lamented the loss of public unity and momentum around food insecurity since the surge of interest during the pandemic. There was still optimism, based on the fact that many members of the public quickly rose to the challenges presented by COVID-19, along with questions about how to convince citizens to care today.

Some underlined the need to nurture empathy and moral action; others stressed the necessity of a pragmatic approach founded on a cost-benefit analysis that would appeal to people’s economic interests. Many agreed that a combined strategy would be most effective. Looking toward the upcoming federal election, the roundtable argues that, rather than working independently, a coordinated communication strategy positioning universal food security as the prerequisite for a healthy society and thriving economy, was more likely to be effective.

The responsibility of government

The principle of food security as a human right was ever-present at the roundtable, especially as related to the role of government in addressing the current emergency. Several members argued that governments need to play a greater role in managing the root causes of food insecurity.

The roundtable referred to governments’ rapid policymaking during the pandemic as proof of the feasibility of quick action to meet the current emergency.

There was discussion about reversing the longtime trends of putting the burden on individuals and charities to meet the food accessibility gap, relying on goodwill instead of pushing for government action.

The roundtable referred to governments’ rapid policymaking during the pandemic as proof of the feasibility of quick action to meet the current emergency. Some participants suggested that the need for a rapid response to economic uncertainty created by American tariffs could drive meaningful policy changes.

The need for better collaboration and novel approaches

Some participants were critical of organizations within the food security sector – including their own – for operating in silos. There was broad agreement that improved collaboration would lead to increased efficiency and effectiveness, particularly in advocating for policy change.

The roundtable also considered the value of expanding food bank offerings to include urban agriculture and cooking programs, something that’s been done successfully at select organizations. Food sovereignty — the right for communities to access and produce their own food sustainably and locally — was also put forward as an important and meaningful goal. (To learn more about Food Sovereignty, view The City of Toronto’s Toronto Black Food Sovereignty Plan [PDF].)

Leveraging the strengths of individuals who are experiencing food insecurity and empowering them to participate in and lead advocacy efforts was seen as key. Participants argued that frontline programming is not just about providing people with food, but about developing relationships, promoting agency and ensuring those directly affected by food insecurity are centered in voices advocating for solutions and developing policy.

***

Looking ahead, Dean Williams said that the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work intends to continue the conversations started at the roundtable and create new partnerships in research, advocacy and education.

“Social workers are in so many places where food insecurity is an issue. We want to make this something that people are learning about, thinking about and acting on from the time they’re social work students until they’re out in the field.”

By Megan Easton

Voices from the Roundtable

“In a lot of the Indigenous populations that I work with, children don’t eat all day long, nothing. Or adults or mothers that are protecting their children don’t eat all day long. It’s a really serious issue in a lot of our Indigenous communities, including urban Indigenous populations.”

— Anna Banerji, Associate Professor, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto

“The band-aid solutions are important, but they’re not the only solution . . . Supportive employment can break the cycle of poverty, creating more food security.”

— Gurbeen Bhasin, Founder and Executive Director, Aangen

“It’s not just about food security and emergency food access. We have community kitchens and other programs. We’ve got our urban agricultural programs as well – gardening, giving people access to land.”

— Jasmine Ferreira, Director, Programs and Evaluation, The STOP Community Food Centre

“Climate change is not being considered well enough. Rising sea levels may have a devastating effect on global agriculture due to soil salinity and other factors. Presently we think of food insecurity primarily as a distribution problem, but we may well be on the cusp of major production issues.”

— Matt Johnstone, Executive Director, FoodShare, Toronto

“We serve 80,000 meals each year, which is quadruple the capacity of the Scotiabank Arena. But we also have community kitchens and gardening programs where we give people access to land to grow foods that are familiar to them. Bringing people together around food is one of the best ways to reduce barriers.”

— Shae London, Executive Director, the STOP Community Food Centre

“A really exciting new initiative this year alongside the student food bank has been a biweekly event where a lot of students come and they’re able to buy groceries at much more affordable rates than they can find at the supermarkets. We’re having a lot more high-level conversations on how we can change the strategic direction of the student union to engage in more long-term initiatives to combat food insecurity.”

— Shehab Mansour, President, The University of Toronto Student Union Food Bank, Executive Committee – UTSU – University of Toronto Students’ Union

“One of the areas that I found very problematic … is not only the issue of food insecurity, but nutritional insecurity and nutritional safety . . . Whether individuals are homeless on the streets or in shelters, there are negative health impacts and health outcomes …. [from] foods that are served in some of the places that they have no option but to access.”

— Volletta Peters, PhD, Executive Director, Sistering

“We need to be better at mobilizing the people who are experiencing the issues . . . If you can put folks that you’re working with first in the conversation, that will be even better . . . I think we can do better working together. Frankly, we’re very fractured. We have our own little empires that we deal with. And that’s not helpful for the people who we care about the most.”

— Nick Saul, CEO, Community Food Centres Canada

“I don’t think food insecurity is a food problem . . . I don’t think food programming is the solution to it . . . I don’t think the way forward is the path that we have taken so far. I really hope that this is the beginning of a very radical rethink about the nature of the problem and our response.”

— Valerie Tarasuk, Professor, Department of Nutritional Sciences, University of Toronto

“We’re collaborating with partners to really help build those important bridges relating to food sovereignty work and community-led food initiatives.”

— Judith Barry, Co-Founder & Government Relations Director, Breakfast Club of Canada

“Indigenous people here in the city are going through a hunger crisis, but so are Indigenous people in northern communities because of accessibility of food. At Kids Against Hunger, we’ve distributed about five million meals to areas of crisis. Two-thirds of them have gone overseas, but we’ve directed one-third to northern communities. I was up in Sioux Lookout delivering 1,400 meals last week . . . We’re trying to feed our people the best we can.”

— Levi Sampson Beardy, Board Director, Action Against Hunger Canada, GTA; Senior Pastor, Aboriginal Believers’ Church

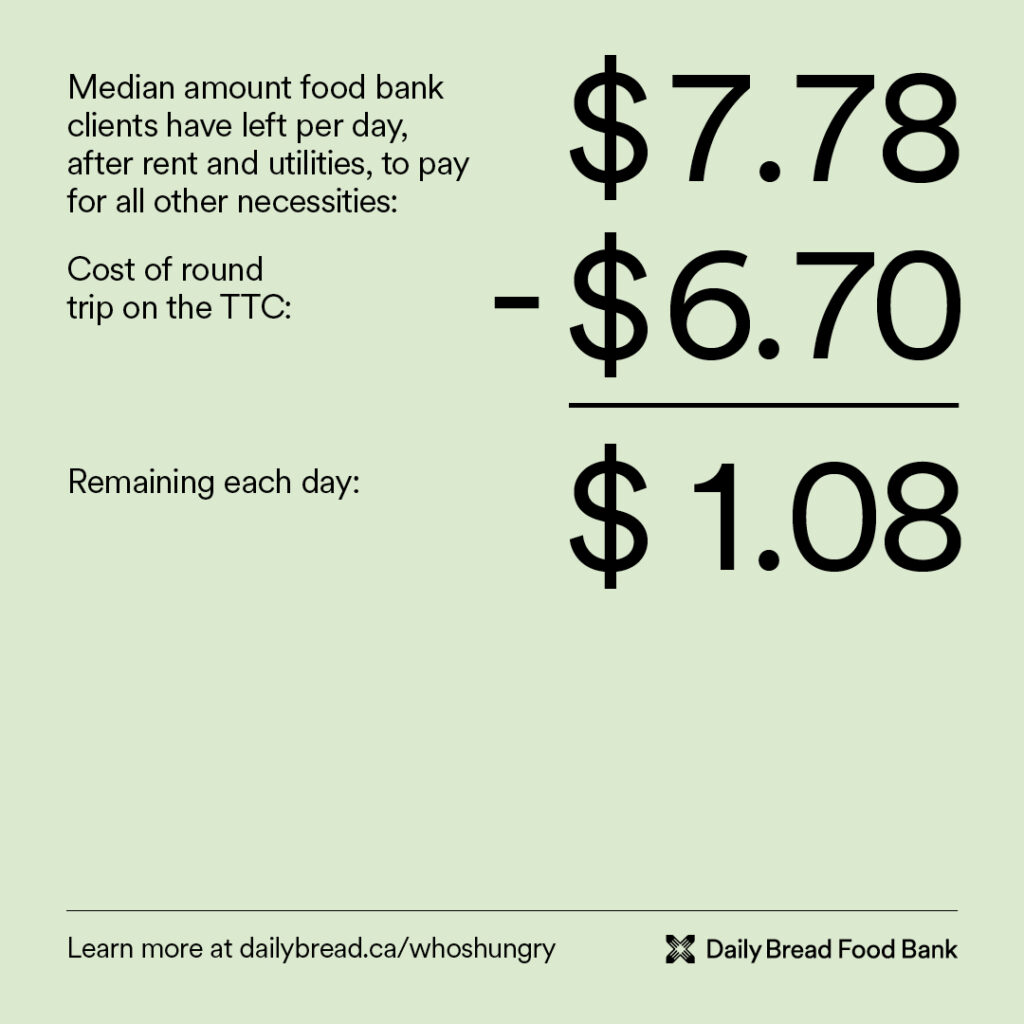

“Right now, more than one in 10 Torontonians has to make use of food banks . . . I’m embarrassed as a Torontonian that we have come to the state that we’ve come to . . . My job primarily is around heightening awareness about affordable housing, income supports and precarious employment. And then almost my secondary job is having to go from distributing about 135,000 meals a week in Toronto through the Daily Bread Food Bank to just under a million meals per week.”

— Neil Hetherington, CEO, Daily Bread Food Bank

“When we searched our souls for what other role we could play in this space, we realized that helping an individual become employed has ripple effects for them, their family and their kids. So we run pre-employment programs such as paid internships for folks to learn the business of food preparation.”

— Cari Kozeriok, Executive Director, Ve’Ahavta

“One of the big things we know is really important in addressing the health injustice realm of mental illness is food security . . . We’re really seeking a recovery-based model. A key to that is wraparound support in food security, stable housing and employment when patients transition out of the centre.”

— Anne-Marie Newton, Chief Philanthropy Officer, Centre for Addition and Mental Health Foundation

“I’m interested in the opportunity to examine how best practices from an international programming perspective can help inform a conversation about food security here in Canada, and vice versa.”

— Vanessa Rich, Humanitarian Project Manager, Action Against Hunger Canada

“We see firsthand how a lot of our racialized and marginalized communities are disproportionately impacted by food insecurity . . . Sometimes it comes down to paying rent or buying food. A client once shared that she was eating bread and ketchup, until she accessed our food security programs, because she wanted to make sure that her kids were supported first and foremost.”

— Tharnya Sivanithy, Director, Population Health, Women’s Health in Women’s Hands

“Last year our network of food banks served a million people over 7.6 million times . . . Food banks are very much straining under the weight of what is happening, which I think really demonstrates that we’re not a solution and rather a temporary measure . . . We have a role to play in helping to make sure we know what’s driving people to access food banks and make recommendations for change. Right now our work is focused on social assistance, advocacy, housing and rent control, as well as good labour laws.”

— Carolyn Stewart, CEO, Feed Ontario