Q & A: Jheanelle Anderson (MSW 2020) on realizing structural changes and forming community at the intersection of Blackness and disability

Categories: Alumni + Friends, Leadership, Q & A, ResearchIf you were to ask Jheanelle Anderson (MSW 2020) to share the key to her success, she’d likely say that it all boils down to forming community. Her journey from social work student to accessibility advisor, researcher, project coordinator with The Centre for Research and Innovation for Black Survivors of Homicide Violence and advocate for Black people with disabilities grew out of opportunities that arose from the groups she joined and the ties she formed as a student. Her work now demonstrates the many levels of practice available to those with a degree in social work.

The recent graduate is making a difference in the lives of individuals on a micro and macro level, working one-on-one with students through U of T’s Accessibility Services and spearheading new research that is building our understanding of the barriers faced by those who are both Black and living with disability. This month she is transitioning to a new role at the City of Toronto as a Policy Development Officer, where she’ll help build policies to support Equity, Diversity, Inclusion and Accessibility within the Children’s Services division. We asked Anderson about her recent projects, what inspired her to pursue social work and the role models who influence her work.

What inspired you to study social work?

What inspired you to study social work?

I grew up in Jamaica and came to Canada in 2008. In my journey as a kid with a disability, I had help along the way, and I wouldn’t be where I am today without that support or community. That really inspired me to pursue this field.

There was oppression in Jamaica, and, growing up, you assumed Canada would be like a utopia. In reality, you see similar injustices here, they just play out a bit differently. I wanted to make a difference and advocate for change that would positively impact on my community, which has been historically and systematically excluded.

What drew you to the Human Services Management & Leadership field of study?

I was going back and forth between this and the social justice stream and was feeling indecisive. However, I knew that I wanted to do policy work that looks at the intersectional experience of Black Disabled folx. I know much of social work practice looks at change on the micro level, working one-on-one with individuals, families, and community, which is great. But I also saw a lot of opportunities to advocate for structural changes that prioritizes Black Disabled folx through policy that addresses systemic inequities. I thought, oh no, should I have done a Master of Public Policy? Then I had a really good conversation with Associate Professor Micheal Shier, who walked me through the many opportunities available in the stream to learn how to develop and inform social policy. In this stream, I learned foundational skills, particularly in program evaluation, stakeholder engagement, and change management. I was later able to build on these skills once I entered the field post-grad and incorporated a Culturally Responsive Evaluation (CRE) framework that informs my work in uplifting the diverse experiences of historically excluded populations.

As a student you were highly engaged in a number of initiatives, which included siting on three advisory committees at U of T. What advice do you have for current and future students who hope to balance academics with co-curricular activities? How did these experiences influence your learning?

All the committees I’ve worked on reflected my identities or lived experiences. I was involved with immigration settlement, disability, and Equity, Diversity, Inclusion and Accessibility (EDIA) work. There are fewer people like me who are Black and disabled within the MSW program, which can sometimes be isolating. When you have historically marginalized and excluded identities within white colonial structures, it is so important to form community.

During my involvement with the advisory committees, I was able to make many linkages to what I was learning in the program. There were many “aha moments,” where I was like: oh, so this is what they meant by that! When I transitioned to the Human Services Management & Leadership stream, many of the theoretical concepts started making more sense because I gained experience serving on boards and committees within grassroots, nonprofit, and educational settings. I was engaging in a practical way as I could incorporate things I was learning in the classroom. I was also learning so much being a part of these initiatives and committees and felt confident bringing forward my expertise grounded in my lived experience and knowledge.

Could you tell us about your role as a Research Assistant and Project Coordinator at The Centre for Research and Innovation for Black Survivors of Homicide Victims (A.K.A. The CRIB)? Is there a particular project you’ve been involved in that you’re proud of or excited about?

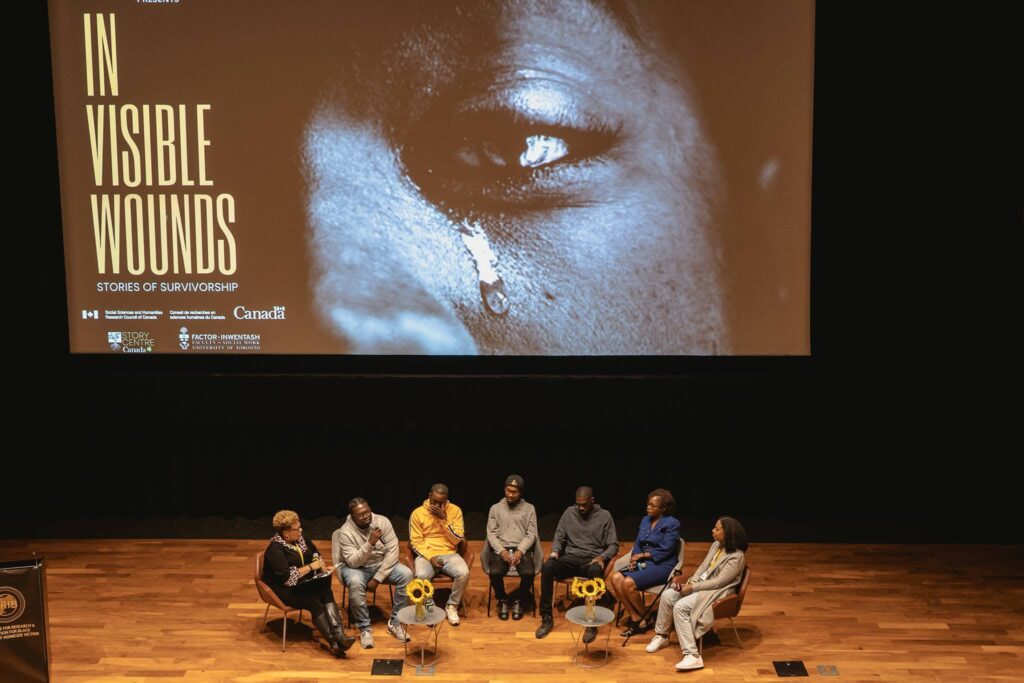

A screening of the digital stories created through the Invisible Wounds project took place at Innis Town Hall on September 13, 2022. Jheanelle Anderson (seated far right) took part in the panel discussion that followed with Dr. Tanya Sharpe (seated far left), the filmmakers and community members.

I started as a Research Assistant, which helped build my capacity to conduct qualitative and community-engaged research. Later, I stepped into the Project Coordinator role for Invisible Wounds, which was such an amazing and very validating experience.

When The CRIB’s founding director, Dr. Tanya Sharpe, came to U of T, I knew I had to get involved. The work being done at the CRIB is truly unique within academia and Canada. I’m also a survivor of a homicide victim, my brother. Being able to talk about this experience has been validating because there’s so much shame, blame, and judgment associated with being a Black survivor, which is rooted in anti-Black racism. Through this project, I’ve been fortunate to have had the opportunity to collaborate with other Black survivors, learning about their experiences post-homicide and how they have navigated survival, which reaffirmed the importance of this work.

The Invisible Wounds project was developed to hear directly from Black survivors of homicide victims on how experiencing the homicide of a loved one has affected their mental, physical, and spiritual wellbeing and to learn about strategies they have used to cope with these traumatic experiences. We worked with neighbourhood ambassadors in Toronto who supported in the co-design of some of our research tools, including the interview guide and recruitment strategy, and they were instrumental in participant recruitment. We held focus groups, which were co-facilitated by our neighbourhood ambassadors. The project also included a digital storytelling workshop, which brought together Black survivors of homicide victims who created short films about their experiences of survivorship and coping. Their stories are so important to tell as it disrupts stereotypes and mainstream portrayals of Black survivors and Black homicide victims.

One of the things that came out of the project was the realization that it’s never ending for Black survivors. It doesn’t just start and stop; it’s ongoing, and we are continually processing our grief while being impacted by anti-Black racism constantly. There were several homicides that occurred throughout this project, which significantly impacted many of the people who participated. So this really cemented the importance of this work and the importance of availability and access to culturally responsive supports and resources for Black survivors.

In 2020 you wrote and published the report “The Intersection of Blackness & Disability in Canada: A Brief Overview & A Call to Action” on behalf of the ASE Community Foundation for People with Disabilities. How does the failure to recognize intersecting identities affect Black Canadians with Disabilities? What has the response to this report been so far?

In my report, which I wrote for ASE Community Foundation, I highlighted the gaps in the disability sector, which often excludes the experiences of Black disabled folx. While we have some data on people with disabilities and some data on the experiences of Black Canadians, there is a lack of data on people with these intersecting identities. We know that poverty is often disabling and exacerbates disability, and disability often leads to poverty because of structural ableism, purposeful exclusion, and denial of access to opportunities and resources. We also know that poverty itself is very racialized. Given these statistics, one could draw some conclusions. For example, we know that Black and racialized people are more likely to hold precarious jobs, often linked to poorer health outcomes, such as developing chronic health conditions. We are making these links with the siloed knowledge we have.

In my report, which I wrote for ASE Community Foundation, I highlighted the gaps in the disability sector, which often excludes the experiences of Black disabled folx. While we have some data on people with disabilities and some data on the experiences of Black Canadians, there is a lack of data on people with these intersecting identities. We know that poverty is often disabling and exacerbates disability, and disability often leads to poverty because of structural ableism, purposeful exclusion, and denial of access to opportunities and resources. We also know that poverty itself is very racialized. Given these statistics, one could draw some conclusions. For example, we know that Black and racialized people are more likely to hold precarious jobs, often linked to poorer health outcomes, such as developing chronic health conditions. We are making these links with the siloed knowledge we have.

After my report, Employment and Social Development Canada reached out about building on my previous work. As a result, I co-led ASE’s Capacity Building Research Project, a Canada-wide environmental scan of services supporting Black and racialized persons with disabilities and co-developed an engagement strategy to improve the social inclusion and full participation of Black and racialized persons with disabilities in Canada.

One key theme from our interviews with service providers is that very few disability organizations were engaged in intersectional work on race and disability, and those that were engaged in this work were primarily grassroots and led by Black and or racialized disabled people or Black and or racialized caregivers on a voluntary basis and with limited resources. Therefore, a critical call to action was that funding should prioritize Black and racialized disabled people already doing this work and support by building organizational capacity and infrastructure to continue doing this work sustainably and long term.

You have also been working at U of T as an Accessibility Advisor. Could you briefly tell us about that role?

I work primarily with undergrad students as an On Location Accessibility Advisor at University College. My role involves working with students with disabilities to develop an accommodation plan based on their needs. I try to incorporate a disability justice lens in my role and support students in reframing disability and navigating the institution. I find that some folx sometimes place a lot of blame on themselves and minimize the barriers they experience as they navigate academia as disabled persons, which is rooted in ableism. I want to help them shift their thinking from a deficit model of disability to a social model, which shifts the blame to the environment and societal attitudes and acknowledges that there are multiple valid ways of participating in society.

Is there a social worker you look up to? Who inspires your work?

I’ve worked closely with Dr. Sharpe, who influenced my approach to community-engaged research with systematically marginalized communities. She has been a trailblazer, advocating for culturally responsive services, research, and policy change for Black survivors of homicide victims.

Imani Barbarin, who uses the handle Crutches and Spice on social media, is another one of my role models. She’s a Black disabled woman and has been doing a lot of work highlighting the intersection of race and disability and creating spaces across social media for disabled people to be in community, be validated, and talk about their experiences navigating ableism systemically and interpersonally.

Sarah Jama is another person I look up to. I got introduced to her in my first year of the MSW program when I was part of the Student Advisory Committee for the annual Hanock Lecture Series at Hart House. The focus of the lecture was on disability, and I really wanted to hear from someone who could speak about the intersection of Blackness and disability. So, I did a massive Google Search, found Sarah Jama and put her name forward. She came to speak, and ever since then, I have been influenced by her work and advocacy. That’s how I got involved with disability justice and joined Disability Justice Network of Ontario, where I’m now a co-chair.

Related:

- Celebrating Black History and Liberation

- Invisible Wounds: Stories of Survivorship foregrounds the experiences of those who have lost loved ones to homicide violence in Toronto

- Keith Adamson appointed Deputy Director at the University of Toronto’s Centre for Teaching Support & Innovation (CTSI)

- A new report and interactive map from The CRIB illustrates the disproportionate prevalence of homicides in predominately Black neighbourhoods in Toronto