New research on the complex factors that shape COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among racialized sexual and gender minorities aims to build trust in the health-care system

Categories: Notisha Massaquoi, Peter Newman

At a time when vaccine passports and mandates are on the rise, two University of Toronto social work researchers are filling a knowledge gap about vaccine confidence and hesitancy in an understudied population.

Peter A. Newman and Notisha Massaquoi in partnership with Toronto Public Health and several community-based agencies have launched a study aimed at gaining a deeper understanding of the pandemic experience of racialized sexual and gender minorities — and the complex factors associated with vaccination decision-making in this group. They’ll ultimately share this knowledge with government, policymakers and community leaders in hopes of both improving pandemic responses and enhancing vaccination rates.

“There’s a common tendency to link vaccine hesitancy with the small but very vocal minority of anti-vaxxers. They aren’t our focus,” says Massaquoi, an assistant professor at U of T Scarborough’s Department of Health and Society with a graduate-level appointment to the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work. “Instead, we’re looking at individuals who face access issues, have concerns based on a history of maltreatment in the health-care system and/or feel that mainstream public health messages don’t speak to their realities.”

There’s ample evidence showing that the pandemic has amplified existing health, economic and social inequities, resulting in COVID-19’s disproportionate effects on racialized groups in Toronto and globally. The same is true for LGBTQ+ communities. Newman and Massaquoi’s VOICES (Vaccine Outreach Integrating Community Engagement and Science) project, funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, is examining individuals in the Greater Toronto Area who hold both identities.

“We’re deliberately focusing on people whose voices are rarely included in health surveys, so that their experiences aren’t erased in the data,” says Newman, a professor at FIFSW. Through an online survey and follow-up focus groups, the researchers are collecting evidence for a more nuanced approach to engage with concerns about COVID-19 vaccination in historically disenfranchised groups.

The VOICES project grew out of another initiative co-led by Massaquoi and Newman called “Safe Hands Safe Hearts.” This investigation, now nearing completion, is testing the effectiveness of peer-led online counselling and education in increasing protective behaviours – such as handwashing, masking and physical distancing – and decreasing psychological distress in LGBTQ+ and racialized populations in Canada, India and Thailand.

“Vaccines weren’t available at the start of the Safe Hands study, but as soon as they were our participants started asking questions about them,” says Newman. “These questions led to the natural evolution of the VOICES project.” Half of the VOICES participants will come from the Canadian arm of the “Safe Hands Safe Hearts” study, while half will be new recruits.

Professor Peter Newman (left) and Assistant Professor Notisha Massaquoi (right) receiving their COVID-19 vaccine shots

In large part, the VOICES project is about building trust in the health-care system among racialized sexual and gender minority communities, says Massaquoi. “They’ve had negative experiences in the system, so their hesitancy isn’t only about the vaccine but about their mistrust of a system that hasn’t treated them well, developed programs to meet their needs or ensured there are service-providers that look like them.”

Massaquoi is the former executive director of Women’s Health in Women’s Hands Community Health Centre in Toronto, the project’s main community partner, which provides specialized primary healthcare for Black and racialized women. She and Newman are co-leading the project with Toronto Public Health’s Associate Medical Officer Health Vinita Dubey. Professor Charmaine Williams and Associate Professor Carmen Logie from FIFSW are also collaborators on the project along with faculty members from U of T’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health and universities in the United States, Australia, New Zealand and the UK. The 519, a city agency serving LGBTQ2S communities in Toronto, is also a community partner.

Rather than considering vaccine hesitancy as an individual issue rooted in deficient scientific understanding or irrational beliefs that must be “fixed,” the researchers are exploring the multiple social and structural factors that shape it. This places the onus on governments and public health leaders to adapt these systems and structures to reduce the barriers.

“Going in with a sledgehammer risks further polarizing those who otherwise might still be convinced,” argues Newman, in reference to mass vaccine mandates —a view he has explained in the media in Canada, as well as Europe and Asia. He says that distrust of vaccines and health professionals not only stems from previous abuse or neglect in the health-care system, such as unethical medical research on racialized populations and pseudo-scientific ‘therapies’ for homosexuality, but ongoing discrimination and inequity in society at large.

“Identifying access issues is a crucial first step if public health leaders want to remove barriers,” he says. “There then needs to be targeted vaccine promotion strategies that recognize and address people’s questions and concerns. The distrust and uncertainty in these groups is completely understandable and should be met with respect.”

As a Black researcher heading study teams that include many other racialized and LGBTQ+ individuals, Massaquoi and her colleagues have experienced many of the COVID-19’s negative effects firsthand, including losing family members, contracting the virus, and struggling with stress and isolation. “It’s been a lot to navigate,” she says. “But the response from our participants has been extremely positive and so gratifying. This is a population that’s been left out of most pandemic strategies and interventions, and they’re so appreciative of just being acknowledged. The study demonstrates to them that there are people who care about their wellbeing.”

Once the team has collected data on the structural and social factors associated with vaccine hesitancy, the researchers, local partners and a documentary filmmaker will collaborate to create a professional, yet accessible, video for distribution in the community. “While the final product will be important, the inclusive process of creating the video is also crucial,” says Newman. “By engaging community members in all aspects of production, we’re building mutual respect while also providing education around COVID-19 and vaccination. The same can be said for the whole project. It embodies where we want to go in public health promotion and emergency preparedness.”

The study’s results will not only inform ongoing COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, but also improve planning for future public health emergencies. “There will undoubtedly be other emergencies, for example due to climate change, that will also disproportionally impact racialized and LGBTQ+ communities across North America and the world,” says Newman. “We hope to contribute to a better model of emergency response that recognizes the different issues and concerns in marginalized populations.”

By Megan Easton

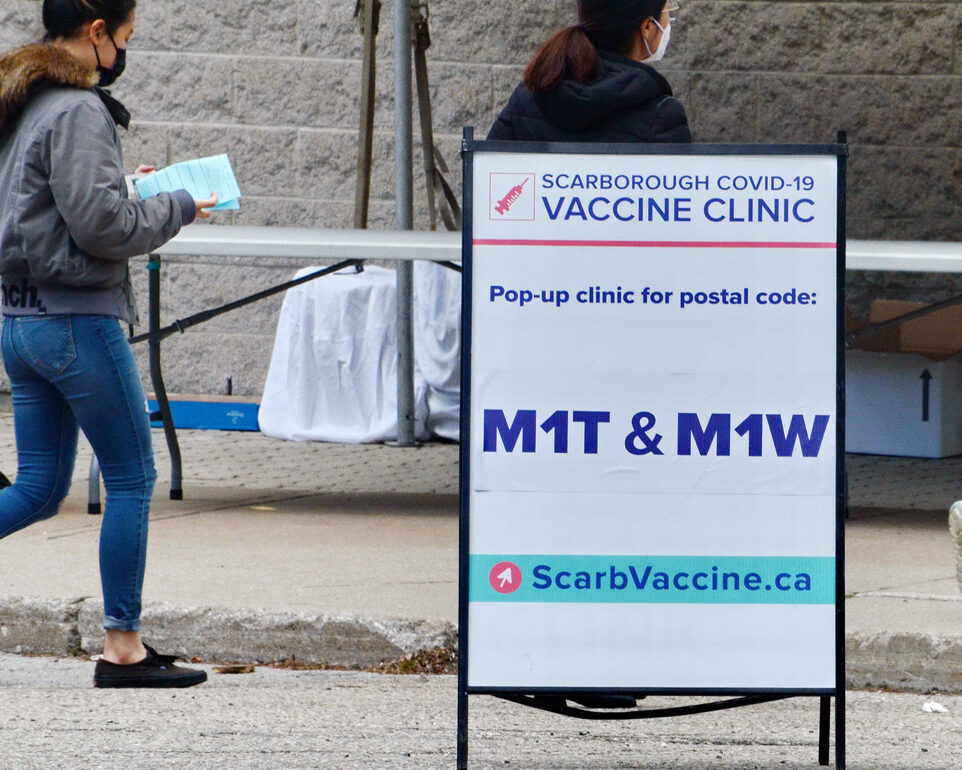

Lead photo: Scarborough, Ontario, Canada, May 6, 2021: People wait in line for a Covid-19 vaccine at the pop-up vaccine clinic at L’Amoreaux Collegiate, 2501 Bridletown Circle in Scarborough, Ontario, Canada. Credit: Bob Hilscher via iStock

Related:

- Notisha Massaquoi joins U of T as an Assistant Professor in Health Education and Promotion

- Q & A with Notisha Massaquoi

- Peter Newman explains why a “one size fits all” approach to the pandemic further marginalizes those who are LGBTQ2SIA+

- Peter Newman and Adrian Guta consider the pros and cons of mandatory COVID-19 vaccination and vaccine promotion