Talk It Out, Work It Out marries mental and physical health in a joint program created and run by U of T social work and kinesiology professors and students

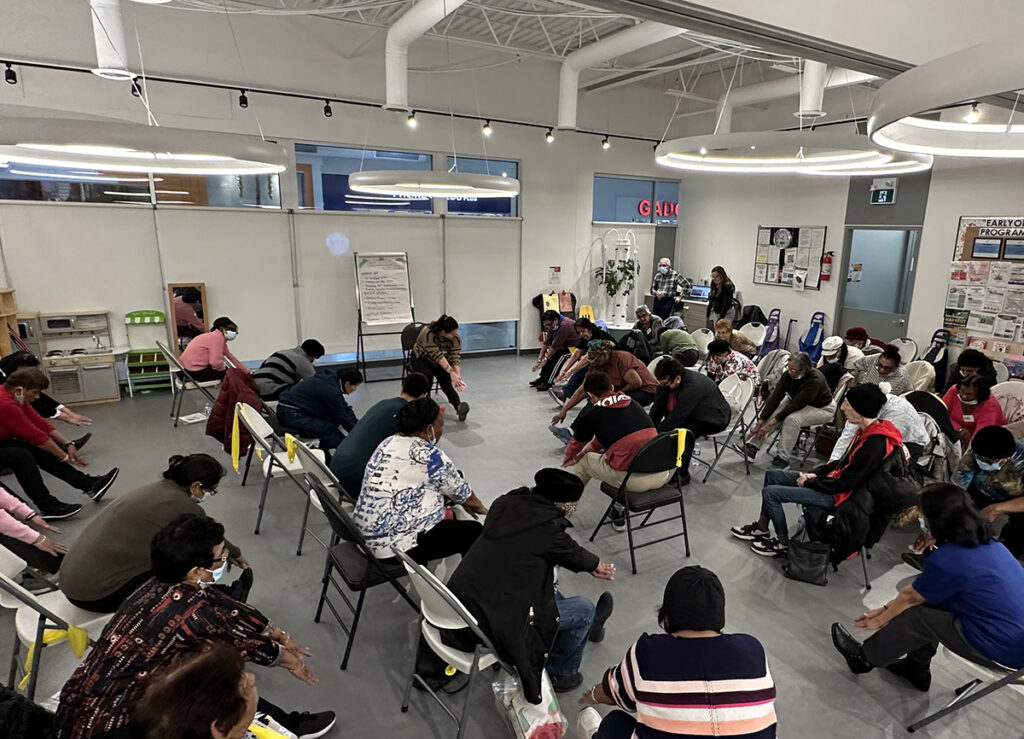

Categories: Alumni + Friends, Faculty, Lin Fang, Partners, Programs + Teaching, StudentsIt’s Friday morning and the Jane/Finch Centre is rocking to the soca groove of Kevin Rougier and Mr. Legz.

Inside, the revelers, all of them seniors, are up out of their chairs. One 83-year-old woman, encouraged by a livewire program worker named Sandra Anderson, is leading a dance of joy.

“A lot of these people live alone,” says Anderson, a senior herself. “This is their escape.”

And then something magical happens. Gradually, organically, the participants doing exercises begin to sync up. What had started as a roomful of individuals, each in their own bubble, has become one thing, a team, a troupe.

Anderson is a little in awe. “I’ve seen so many seniors who couldn’t move, wouldn’t move, and now I look at them and oh my goodness,” she says. “The stretching, the rubber-band work. That is a tribute to the Talk It Out, Work It Out team that came and showed them the techniques.”

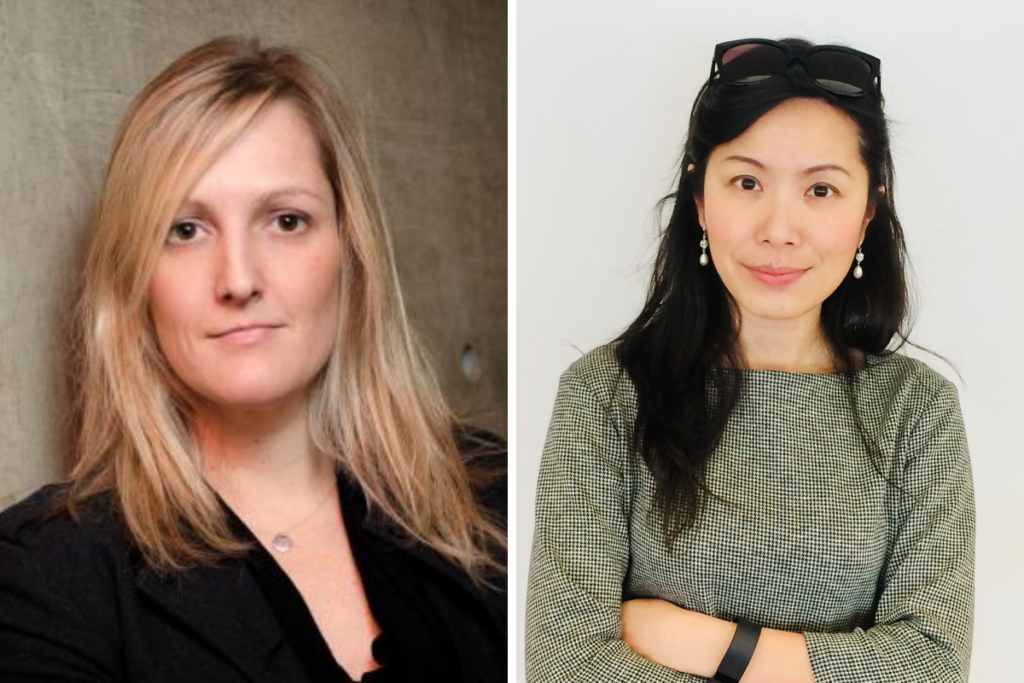

Talk It Out / Work It Out is a groundbreaking pilot project partnering two University of Toronto brain trusts: the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work and the Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education. Graduate students from each contributed jointly to the curriculum that clients at the Jane-and-Finch seniors enjoyed.

“Work It Out,” the sweaty part, is the bailiwick of kinesiology grad students. When the exercise is done and heart rates are returning to baseline, specially trained Master of Social Work students shepherd the clients into small groups, where they share their concerns to the degree and depth they choose. That’s the “Talk It Out” part. (The third point of the triangle is the community partner, in this case the Jane/Finch Centre, which delivers the clients to the academics with a “warm handoff” of earned trust.)

Over seven 1.5-hour sessions, comfort-level rises, anxieties are de-fanged, and the double-strength action of expert tutelage and peer support delivers its therapeutic payoff. “We planned it this way so that seniors could first get activated through exercise,” Lin Fang, associate professor of social work and Factor-Inwentash Chair in Children’s Mental Health at FIFSW, says. “Later on, as seniors were used to the Talk It Out section and needed more time for it, we switched it around so that they could have time to speak first. The program was designed to be fully integrated.”

***

The origin story of Talk It Out / Work It Out begins at the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, in the early months of the pandemic. A severe mental health crisis was growing in the shadow of COVID, and Fang was feeling “paralyzed and powerless” in the face of it. Hardest hit were marginalized communities, where isolation, anxiety and depression were rampant.

Fang had the idea of harnessing the knowledge and skills of Master of Social Work students to help communities that were struggling to access support. To develop the program, she first knocked on the virtual doors of community agencies, who might be willing to collaborate. After some extensive consultations, Partnerships ensued and the Talk It Out Clinic was born. Students, under the supervision of professional staff and faculty members, were trained to provide free counseling sessions, via telephone or a secure online platform, to those distressed and stuck indoors. The initiative was a baby step toward what professor Fang hoped would eventually become a full-fledged system of care, if not a rethink of how social work schools and community organizations can work together to strengthen grassroots mental health-care delivery.

For the social-work students, the practical community experience was a godsend. They’d been given the opportunity to use what they’d learned in their classes, out in the “living lab” called the real world. Plus, it would count toward their practicum: Win-win!

To professor Fang, Talk It Out was absolutely on point with for the faculty’s mission “to increase our community impact through training and service.” And it drew deeply from her research on mental health in racialized communities. But there were still factors hampering its potential. For example, it was apparent that some of the most at-risk groups still weren’t getting the help they needed. Many great candidates for the program didn’t want to go for therapy. For a lot of reasons, many seniors won’t go to counseling – even if it’s being offered for free. Sometimes you need to sweeten the pot.

Enter Catherine Sabiston.

As professor of exercise and sport psychology and Canada Research Chair in Physical Activity and Mental Health, she knows what a powerful elixir exercise is, not just for the body but for the mind. There are now more than 100,000 peer-reviewed studies showing that physical exercise has mental-health benefits — from elevated mood to reduced anxiety to improved focus. Knowing these benefits, Sabiston had spearheaded MoveU.HappyU — an exercise and mental health coaching program overseen by KPE students from her lab to help U of T students manage their symptoms of stress, anxiety and depression. Sabiston integrated the program into a graduate class, giving students a chance to deliver exercise and mental health coaching to peers on campus. It was a little like what professor Fang and her collaborators were doing over in the social work Faculty, but with a greater focus on physical activity.

Professors Fang and Sabiston put their heads together. “Catherine’s team had the know-how,” Fang says. Sabiston et al had already been exporting MoveU.HappyU out into the community, adapting it for a Toronto housing project whose main residents were people with serious mental illness. What if graduate students from Fang’s lab and graduate students from Sabiston’s course teamed up? The new joint effort would marry mental and physical health programming. If it worked, it could create infield placement possibilities for students on both sides.

But challenges remained.

The “priority populations” professor Fang had in mind for these interventions were different from the younger populations that the programs had been developed to serve. These were seniors living in largely BIPOC communities.

“If you go to a program where they don’t seem to understand you – they’re talking differently, they’re singing songs you don’t know – you’re not going to come back,” says Fang. “We had to figure out ways to communicate that would resonate with them.”

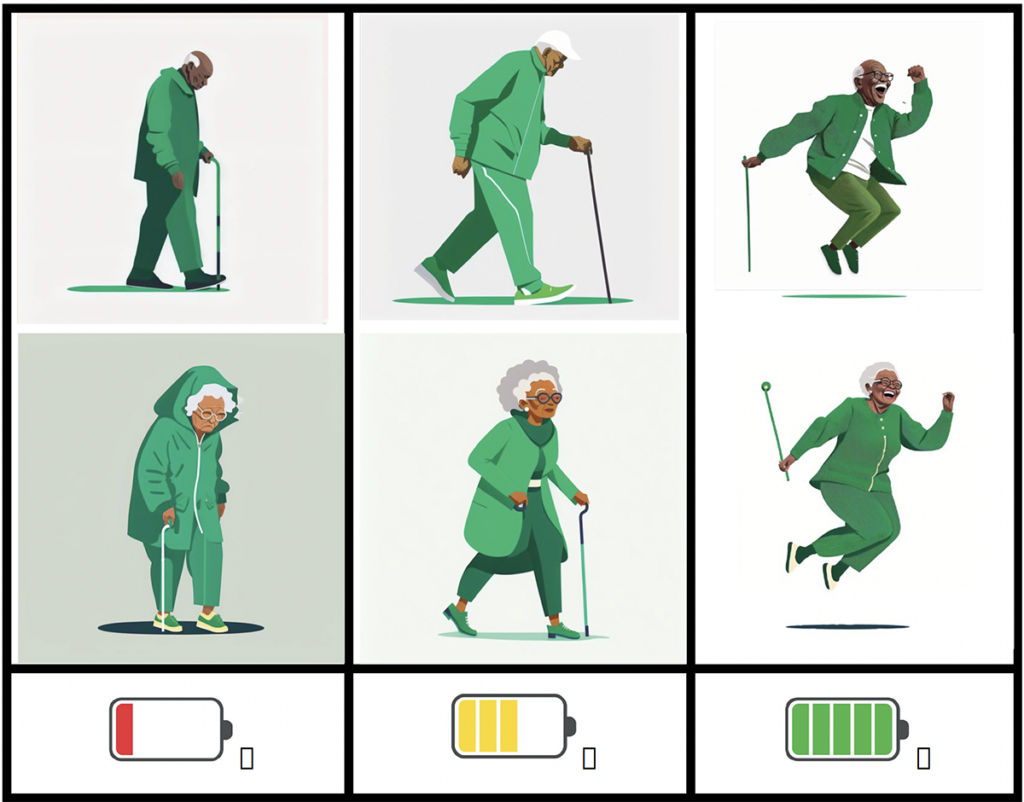

A major cultural-sensitivity retrofit was in order. Many elements of the existing programs would have to be tweaked. For example, the folks pictured in the MoveU.HappyU workbooks were mostly young and White, which wasn’t going to fly. “The way we’ve always delivered these products is the White, Western way,” says Sabiston. Much of the therapeutic language, lingua franca of the academics, would be baffling. “We realized they’re not going to know what this 1-to-7-point Likert scale is,” Sabiston says. “So, we wondered: How can we talk about mood in a way that’s readily understandable?” Why not a little face, from smiley to frown-y, by degrees.

Likewise, clients seemed not so interested in things like goal-setting (a major preoccupation of the younger Western students who had participated in Sabiston’s original trials). But they did want to have more energy. Okay, great: we’ll monitor their energy levels before, during and after. But how to convey that in an instantly graspable way? Why not a picture of a battery. “Either your battery’s dead or it’s fully charged or it’s in the middle,” Fang says.

Even the concept of “therapy” itself would have to be soft-pedalled. “The idea of ‘mental health’ can be new to many people,” says Fang. Stress? It’s the depth of the water they’re swimming in.

“The majority of the participants are immigrants — from Ghana, Guyana, Indo-Caribbean countries,” Fang says. They’ve had hard lives. But they may also have a different narrative around how one deals with life’s setbacks.

“They say, ‘Hey, we just live, we suck it up, we mosey on, it is what it is,’ says Anderson. “Until somebody points out to them, ‘Your blood pressure is up because you are stressed.’ They go, ‘Really? Nah, I think it’s just something I ate.” The idea that stress is something that can actually be something positive, even energizing, if managed strategically, is a foreign concept that’s going to have to be unpacked with gloves.

All teams agreed the program should be client-driven. “We want the seniors to feel like they have agency in the whole process,” says Sabiston. To that end, the Jane/Finch Centre asked the seniors about the personal challenges they would like to overcome. What came back was: ‘I’m lonely.’ ‘I’m anxious.’ ‘I’m in pain.’

That last item made the academics prick up their ears.

A lot of the time (though not always) pain results from prolonged inactivity. Like a car left in the garage, we lock up; we rust. The prescription is to move. But that can be a tough sell to someone who’s in pain. The last thing they may feel like doing is moving – even though it may be the thing that, ultimately, will help them the most.

***

Back at the Jane/Finch Centre, the songs have been sung, the dances danced, the stretch-bands stretched. And now it’s time for the back half of the double-header — the “talk it out” part. Everyone musters up into their small groups.

The subject on the table is social support. “Think about people in your life who prop you up, who give you strength,” the lead facilitator, a Master of Social Work student named Kayleigh Gladstone, says. Some of the seniors seem eager to share. Others write their answers down. A second student, Deanna Gooden, casts a headwaiter’s eye over the group. If a client isn’t able to read or write, the student will take dictation into a book that the client can keep when the eight weeks are over – a log of their progress. Through those small wins of heart and mind, “they get a confidence and momentum they can take into their life,” Fang says.

Gladstone says she was amazed by the support the program received. “In our first session we anticipated 15 people and we doubled that and each week! These participants truly wanted to strengthen their body and minds,” she says. “And the participants became better and better able to support each other.”

Hadi Mostofinejad, one of the Master of Professional Kinesiology students in professor Sabiston’s course and one of the lead exercise instructors saw support among the participants grow throughout the program as well. Loneliness and isolation were recurring themes that arose in the Talk It Out sessions; many of the seniors lamented the lack of social support in their lives. “Now we are part of your support system,” Hadi told the group, to broad smiles all around. Many of the participants found others to pair up with as “walking buddies” — thereby extending their health journey beyond the walls of Jane/Finch.

Here in the heart of the community, people have synced up not just physically but emotionally. Real friendships have been made.

“That’s the best part of ‘talking it out,” Anderson says. “Everyone has a story. Your story reflects what you’re going through, but I can identify with it, too. By talking we’ve helped each other make it through another day.”

Story by Bruce Grierson

***

| “Talk It Out, Work It Out” is a collaboration among University of Toronto’s Talk It Out Counseling Clinic at the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, the Mental Health and Physical Activity Research Centre at the Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Health, and Jane/Finch Community & Family Centre. We would like to acknowledge the generous support of Joan and Bernard Aaron for this initiative.

The Talk It Out Online Counselling Clinic, an ongoing initiative of the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, is further made possible by generous donations from:

Talk It Out is also funded in part by FIFSW Annual and Leadership donors, who have also had an incredible impact on the program and its students. Visit the Talk It Out Online Counselling Clinic’s website to learn more about the program and its supporters. |