World AIDS Day Q&A: Professor Carmen Logie on HIV prevention, stigma and care among refugee and displaced youth

Categories: Carmen Logie, Faculty, Research

In honour of World AIDS Day on December 1st, we spoke to Carmen Logie to learn about her recent research on HIV prevention, stigma and care among refugee and displaced youth. The Canada Research Chair in Global Health Equity and Social Justice with Marginalized Populations is a leader in HIV research who’s shining a much-needed light on understudied populations, building an understanding of the complex intersecting systems that increase HIV vulnerabilities, and working with communities to develop novel interventions for prevention and care.

In honour of World AIDS Day on December 1st, we spoke to Carmen Logie to learn about her recent research on HIV prevention, stigma and care among refugee and displaced youth. The Canada Research Chair in Global Health Equity and Social Justice with Marginalized Populations is a leader in HIV research who’s shining a much-needed light on understudied populations, building an understanding of the complex intersecting systems that increase HIV vulnerabilities, and working with communities to develop novel interventions for prevention and care.

What inspired you to study HIV prevention among refugee youth? As you say on your podcast, take us back in your time machine!

When I finished my PhD in 2010, I was thinking I would do a relaxing postdoctoral fellowship: I’d do data analysis; I’d do a lot of yoga; I’d sit in cafes and do writing. But then at that year’s Council on Social Work Education, my friend and colleague Dr. Carolann Daniel at Adelphi University invited me to come to Haiti and work with her because I do HIV work and the HIV clinic there had been destroyed by the earthquake. So, we applied for a Grand Challenges Canada grant together, and we came up with a plan. We did an HIV prevention study with women who were internally displaced after the earthquake. We also got a CIHR grant to work with displaced youth on their prevention needs. Being involved in this work inspired a passion to do more with forcibly displaced people.

Fast forward several years to 2017. I was working with a PhD research assistant, now Dr. Moses Okumu, who is from Uganda. At that time, there were a lot of refugees coming into Uganda from South Sudan. We were chatting about it, and I shared my experiences doing research in Haiti with displaced people. I said, if you ever want to do something similar… and he said: let’s do it. So, in 2018, we started our first project with urban refugee youth in Kampala, in collaboration with Young African Refugees for Integral Development.

Fast forward several years to 2017. I was working with a PhD research assistant, now Dr. Moses Okumu, who is from Uganda. At that time, there were a lot of refugees coming into Uganda from South Sudan. We were chatting about it, and I shared my experiences doing research in Haiti with displaced people. I said, if you ever want to do something similar… and he said: let’s do it. So, in 2018, we started our first project with urban refugee youth in Kampala, in collaboration with Young African Refugees for Integral Development.

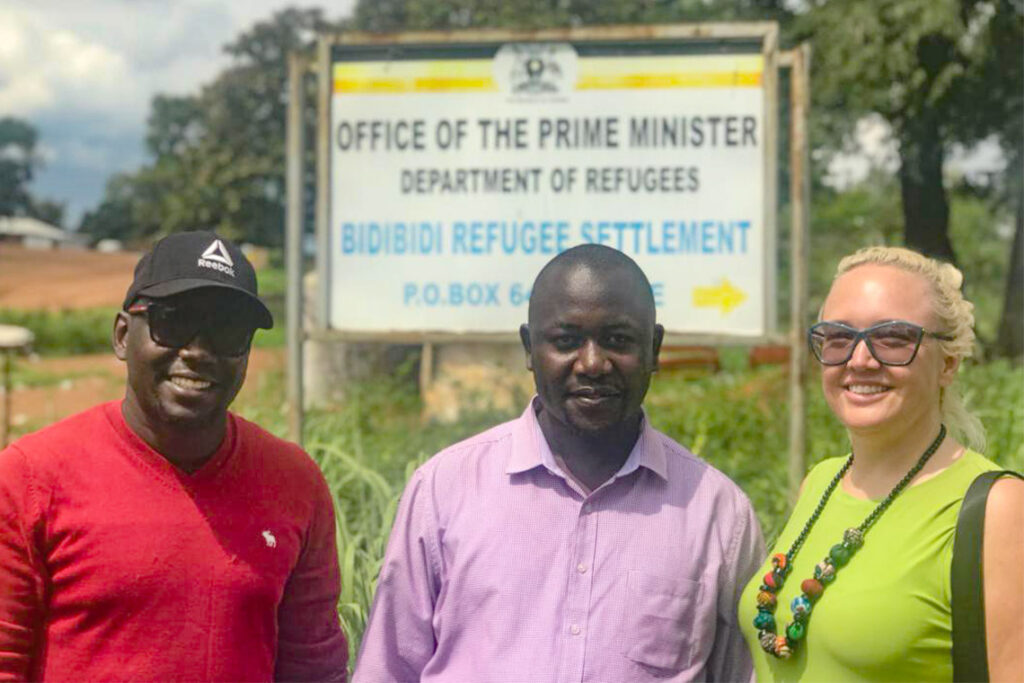

Photo: Carmen Logie (right) and Moses Okumu (left) met with local partners, including Daniel Wakibi, director of programs for Real Medicine Foundation Uganda (photo courtesy of Carmen Logie)

In the context of the United Nation’s goal to end AIDS by 2030, why is it so important to study these communities?

There’s been very little HIV research with refugee and displaced youth. These are people who experience multiple vulnerabilities and demonstrate numerous strengths. They also have unique experiences and needs that shape their risks for HIV. Many of them experience cumulative violence: violence that forces them to leave a country, violence in the refugee journey, and violence in the urban or refugee settlements where they now live. They often live in communities, such as those in Uganda, with scarce resources, poverty, and often water, food and sanitation insecurity. And all of these things are drivers of HIV.

We’ve never had so many forcibly displaced people, which includes refugees — ever. And the numbers are just increasing. But I don’t want to paint a picture of refugee and displaced youth as being hopeless victims, because there’s a lot of strength within these communities, and we are always trying to apply a strength-focused approach. We’re always asking refugee and displaced youth for the solutions — and they have so many. In 2017, for example, we trained 12 refugee youth peer navigators in Kampala who have been working with us now for more than five years. They are really the key to successfully working with refugee youth because they understand many shared experiences, they have connections with refugee communities, they speak different languages, and they understand the different traumatic events during conflict and resettlement.

In June you co-edited a special issue of the American Journal of Public Health titled “Addressing Intersectional Stigma and Discrimination to Improve HIV-related Outcomes.” How does stigma experienced by refugees intersect with other issues to influence HIV prevention and care?

In June you co-edited a special issue of the American Journal of Public Health titled “Addressing Intersectional Stigma and Discrimination to Improve HIV-related Outcomes.” How does stigma experienced by refugees intersect with other issues to influence HIV prevention and care?

Refugees experience intersecting forms of stigma, meaning they may belong to different social categories that are marginalized (such as being young, being women, being refugees) where they have less access to power and resources. They are treated differently because they are refugees, and they often also experienced language barriers and cultural differences in their country of resettlement. They might try to go get an HIV test, and be told, “oh, you’re a refugee, you don’t belong here.” They might also face barriers because they can’t speak the language. If you add on another level of precariousness — for example, if you have refugees engaged in transactional sex and sex work, which is illegal in Uganda — then the barriers increase even more. We’ve interviewed people who worry that asking for an STI or HIV test will hurt their immigration process.

Your research clearly illustrates that it isn’t enough to simply educate people on how, as individuals, they can protect themselves from contracting HIV. We also need to better understand and address the external factors that influence how HIV spreads. Could you share what you have learned, for example, about the relationship between food insecurity and HIV risk?

When women, in particular, are living with food insecurity, it’s often not the only insecurity they’re living with. Food insecurity and housing insecurity often co-occur. A person who is experiencing intimate partner violence in this context might find it difficult to leave because they have nowhere to go or little ability to support themselves. They are also likely to have less power in their sexual relationship — which means they have less control over decision making when it comes to contraception, condoms, and HIV and STI testing. It goes the other direction, too: once a person acquires HIV, especially if this person is a woman, they have a higher likelihood of experiencing intimate partner violence, and they’re more likely to live in poverty — and poverty is one of the root causes of food insecurity.

We have also seen food insecurity linked to HIV risk through migration. When people migrate to access food, it exposes them to new sexual networks. It also increases the likelihood of transactional sex. In these cases, when people are having sex in exchange for food, there’s a lot less power to negotiate condom use or engage in other forms of HIV prevention.

We have also seen food insecurity linked to HIV risk through migration. When people migrate to access food, it exposes them to new sexual networks. It also increases the likelihood of transactional sex. In these cases, when people are having sex in exchange for food, there’s a lot less power to negotiate condom use or engage in other forms of HIV prevention.

Read the recent NPR article “Food insecurity is driving women in Africa into sex work, increasing HIV risk,” which features an interview with Logie and her colleague Dr. Sheri Weiser, co-founding director of the University of California Center for Climate, Health and Equity.]

You are currently involved in two projects that have received funding and that address climate change’s impact on HIV risk. Why is it important to consider climate change in your work?

We just had an article come out in the Journal of Water, Sanitation & Hygiene for Development on the relationship between water insecurity and sexual and gender-based violence among refugee youth. A lot of the refugee girls and young women we spoke to talked about experiencing sexual violence while trying to get water. The further they had to go to get water, the more exposed they would be to sexual violence. We are now doing a scoping review on climate change and its relationship to sexual health. Extreme weather events such as drought, heavy rain, and high temperatures lead to water, food and sanitation insecurity, which are linked to practices such as transactional sex, migration, and substance use — all of which can lead to increased exposure to HIV and reduced access to prevention technologies. Extreme weather events can also lead to other infectious diseases that can either increase people’s chance of acquiring HIV or harm their ability to maintain viral suppression.

You have also been exploring creative interventions to reach refugee youth and engage them on issues related to HIV prevention and care. Could you tell us about your project with comic books?

You have also been exploring creative interventions to reach refugee youth and engage them on issues related to HIV prevention and care. Could you tell us about your project with comic books?

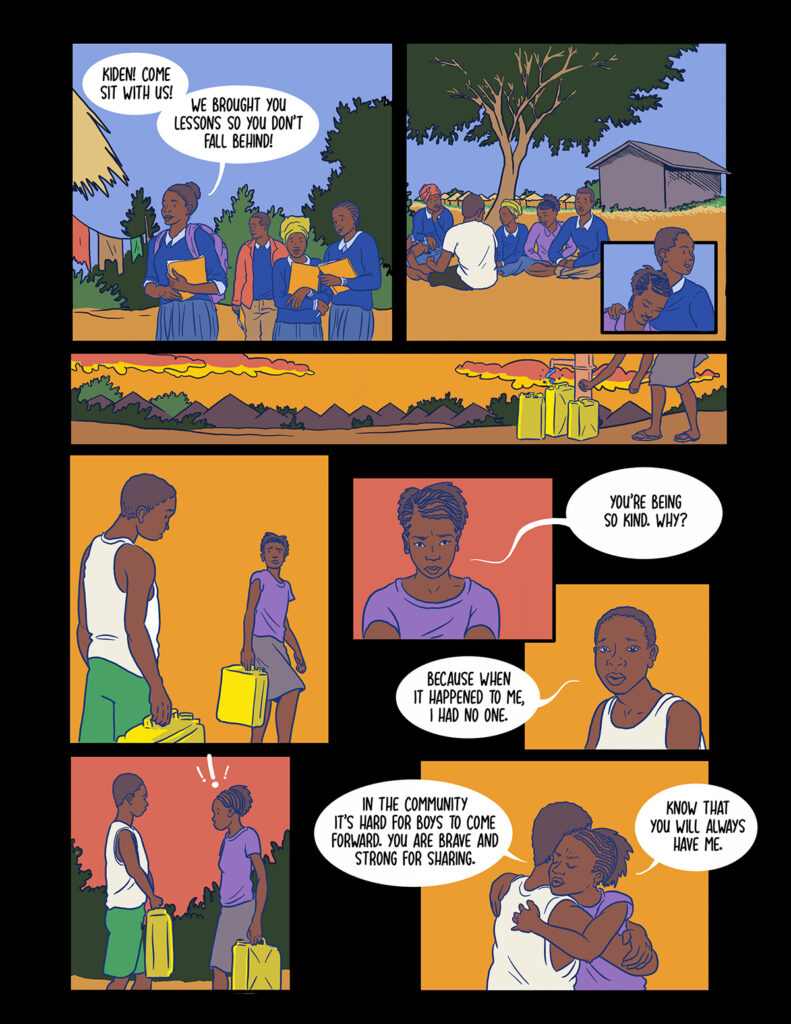

There’s a scarcity of research on post-rape care for forcibly displaced youth in refugee settlements. So, we got a Grand Challenges grant to test an intervention using comic books in Uganda’s Bidi Bidi refugee settlement. We used qualitative data to develop a comic book series (see example, left) that addressed issues like sexual violence,; stigma; bystander efficacy; support for survivors; forced, early and child marriage and so on. We then held a workshop where we read and discussed the comic book scenarios with the youth. Afterwards, we provided the youth a blank version of the book to fill out themselves so they could share their own perspectives and solutions. Our findings were very promising. After the workshop, we found reduced sexual violence stigma and depression, increased bystander practices and resilient coping strategies among other benefits. We are now using comic books in a new HIV testing study in Bidi Bidi.

I am excited about comics, because I think they’re fun for youth. They are low-cost, accessible to those with low literacy and can spark emotion. And there was already evidence that graphic medicine, as it’s called, can be effective in health education. I liked that we were not just providing them with information, we were asking them: how would you complete the story?

Digital versions of the comics are available on the SSHINE Lab website.

Dr. Carmen Logie joined the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work in 2013 as an Assistant Professor and was promoted to full Professor in 2022. She is an Adjunct Scientist at Women’s College Research Institute, an Adjunct Professor at the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment & Health, and a Research Scientist at the Centre for Gender & Sexual Health Equity. She holds the Canadian Research Chair in Global Health Equity and Social Justice with Marginalized Populations.

Dr. Logie has been awarded funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), CIHR Clinical Trials Network, Social Sciences & Humanities Research Council of Canada, Grand Challenges Canada, Canada Research Chairs, and Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI), to lead global research focused on sexual health and rights. She directs the CFI ‘Stigma & Sexual Health Interventions to Nurture Empowerment’ (SSHINE) Lab, collaborates with the World Health Organization (WHO) and was a guideline development member for the WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Self-care Interventions for Health: Sexual and Reproductive Health & Rights, including the Classification of self-care interventions for health: a shared language to describe the uses of self-care interventions.

Dr. Logie has published more than 240 articles, cited more than 9000 times; you can learn more about her publications here and here. She is Deputy Editor at the Journal of the International AIDS Society and on the Editorial Boards for Social Science & Medicine Mental Health and PLOS Global Health. Her latest book Working with Excluded Populations in HIV: Hard to Reach or Out of Sight? was published in 2021 as part of the Social Aspects of HIV Series. In 2020, Dr. Logie launched the ‘Everybody Hates Me: Let’s Talk About Stigma‘ podcast featuring stigma experts from across the world.

Related: