The pandemic forced health-care providers to move to virtual appointments. Rachelle Ashcroft’s research with both providers and patients offers critical insights for the future

Categories: Rachelle Ashcroft, ResearchWhen the pandemic forced family doctors and the other healthcare providers working in primary care teams to suddenly shift to phone and video appointments, Rachelle Ashcroft’s mind began spinning with questions. A social work researcher with a longstanding interest in primary care, she wondered how healthcare providers would manage the change and what it would mean to patients. To find out, she launched several projects that are helping to inform the future of virtual care in Ontario.

“There was very little virtual care offered in primary care teams in the province before COVID-19,” says Ashcroft, who joined U of T’s Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work as an assistant professor in 2016 and has extensive experience as a social worker in multiple health-care settings. “From day one of the pandemic, my research colleagues and I recognized a unique opportunity to learn from the experiences of providers and patients as they navigated virtual appointments. We wanted to find out what worked well and what didn’t, so policymakers and health-care leaders could apply those lessons going forward.”

Assistant Professor Rachelle Ashcroft; Photo by Harry Choi

Ashcroft and her research partners began by seeking the perspective of primary care teams made up of family doctors, nurses, pharmacists, social workers and other health-care professionals. “Much of the early pandemic research focused on acute and hospital-based care, and we weren’t aware of any other studies examining interprofessional primary care practices,” she says. Her research was funded in part by the Ontario Ministry of Health.

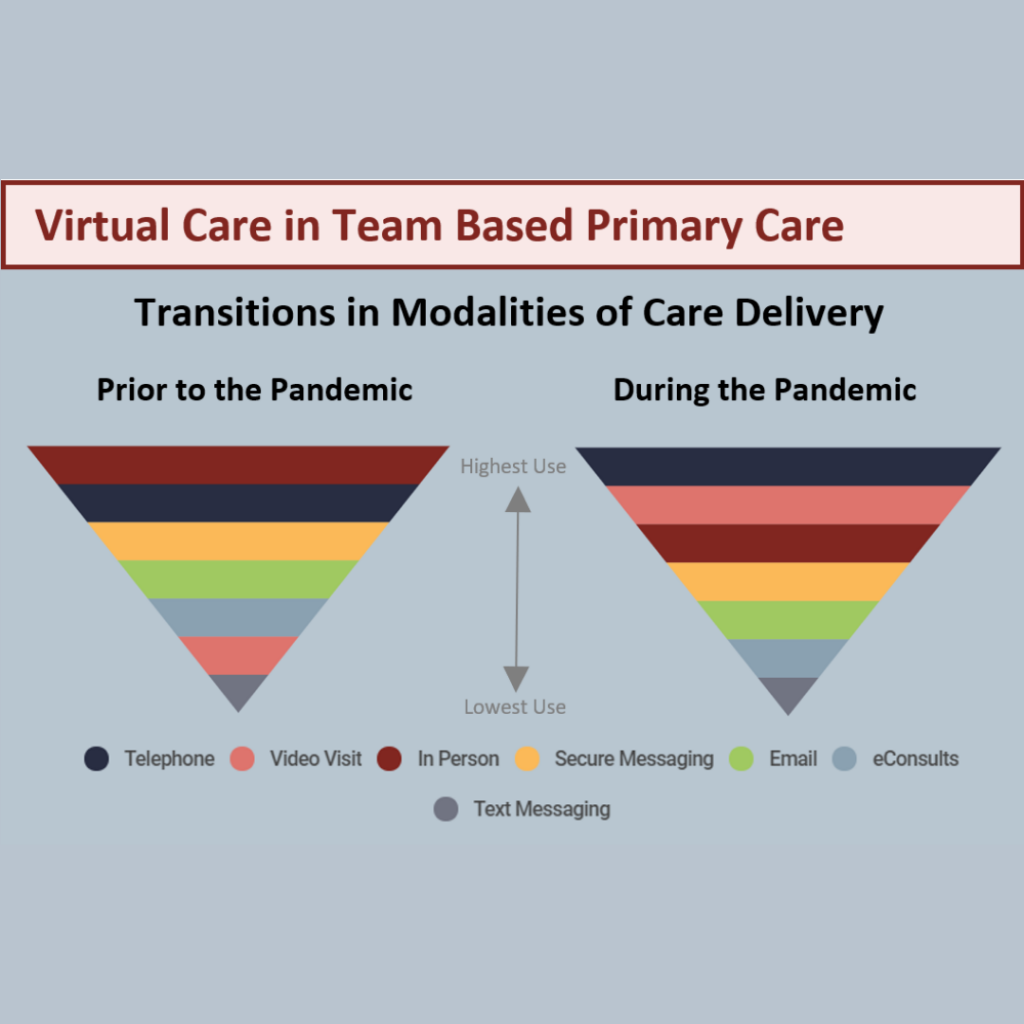

More than 440 providers responded to an online survey. Only 40 per cent of them said they’d received any training for virtual health-care delivery, yet they reported an almost total switch from in-person to virtual care in the early waves of the pandemic. Respondents also said wait times for appointments decreased, and there was a shift in the most commonly seen patient concerns towards mental health and away from chronic conditions such as diabetes and heart disease.

“The insights from providers were crucial, but we had an even bigger knowledge gap to fill: the patient perspective on receiving virtual care,” says Ashcroft, whose research partner is Professor Simone Dahrouge from the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Ottawa. Recent MSW graduate Simon Lam (MSW 2020) is the project’s research coordinator.

Ashcroft, Dahrouge and Lam recruited a Patient Advisory Committee with diverse representation in terms of race, gender, age and geography to help design and implement this phase of the research. “They calibrated our lens to focus directly on the factors that are most relevant and meaningful to patients,” says Ashcroft.

Patient advisers such as Esther Guzha from Toronto and Calvin Young from Thunder Bay helped refine the themes and questions for a province-wide online patient survey and individual patient interviews. “I was asked to comment on the content before the researchers proceeded to the next step of the project,” says Guzha. “I felt that my voice was heard and understood.” According to Young, “the final product was a testament to everyone on the committee being heard.”

The survey and interviews took place between January and March 2021 – intentional timing, says Ashcroft. “We didn’t want to launch in the crisis of spring 2020, when virtual care was just rolling out. We wanted to give patients time to reflect on their experiences.” The researchers used multiple avenues to reach a broad, diverse group of Ontario patients, including social media and internal emails within family practices. In the end, more than 530 patients completed the survey and 55 completed one-on-one interviews.

The survey and interviews took place between January and March 2021 – intentional timing, says Ashcroft. “We didn’t want to launch in the crisis of spring 2020, when virtual care was just rolling out. We wanted to give patients time to reflect on their experiences.” The researchers used multiple avenues to reach a broad, diverse group of Ontario patients, including social media and internal emails within family practices. In the end, more than 530 patients completed the survey and 55 completed one-on-one interviews.

Most patients were satisfied with the quality of care they received virtually and described some benefits over in-person care. “Nearly all the patients agreed that virtual care improved access,” says Ashcroft, whose collaborators included researchers from several Ontario universities, the Ontario College of Family Physicians, Alliance for Healthier Communities, and the Association of Family Health Teams of Ontario. “More than 90 per cent said it was convenient and saved time and money.”

Not surprisingly, patients said that virtual care was particularly good for health concerns that don’t require physical exams or visual assessments, though there was one exception. “Patients were almost evenly divided on whether they thought virtual care worked well for mental health concerns,” says Ashcroft. “We’re now starting a deeper investigation of the place of mental health care in the virtual environment within primary care settings.”

Some of the patient-reported downsides of virtual appointments included privacy concerns, communications challenges (such as a lack of cues from body language on the phone), shorter time slots and difficulty establishing relationships with new providers.

“It makes sense that patients who had known their providers for more than a year pre-pandemic had better experiences of virtual care,” says Ashcroft. “There was a foundation of knowledge, familiarity, and trust.”

Ashcroft and her team have shared their findings with the family practices that participated in the research and created recommendations for Ontario Health. The patient advisers were also involved in these efforts. “I hope that the information gathered in the reports will help create a strong and safe virtual care environment for the health journeys of patients, families and caregivers,” says Young.

The recommendations include offering training in virtual care for providers, developing best-practice guidelines for providers on when to use virtual care appointments, giving patients the choice of virtual or in-person appointments when appropriate, enabling patients to share information such as documents and photos before virtual appointments, asking patients if they want family members to join calls and ensuring providers conduct appointments from private settings.

“The pandemic was the catalyst for virtual care, but we know it’s here to stay,” says Ashcroft, who will soon begin an even larger patient survey on virtual care in Ontario. “This ongoing research is offering critical insights to shape a primary care system that patients want and find most helpful.”

By Megan Easton

Publications

Interprofessional primary care during COVID-19: a survey of the provider perspective

Related:

- How primary health care teams are providing care during the COVID-19 pandemic

- “If social work is to play an important role in change, the public must understand the profession and the challenges it faces,” writes Michael Multan in ‘Healthy Debate’

- Newly funded COVID-19-related research will build knowledge on prevention and care

- Factor-Inwentash Faculty students harnessed their counselling and leadership skills to help develop a new Peer Support Service at U of T