New report on unregulated homestays in Canada uncovers adverse living conditions for international students from Kindergarten to Grade 12

Categories: Alumni + Friends, Faculty, Izumi Sakamoto, Research

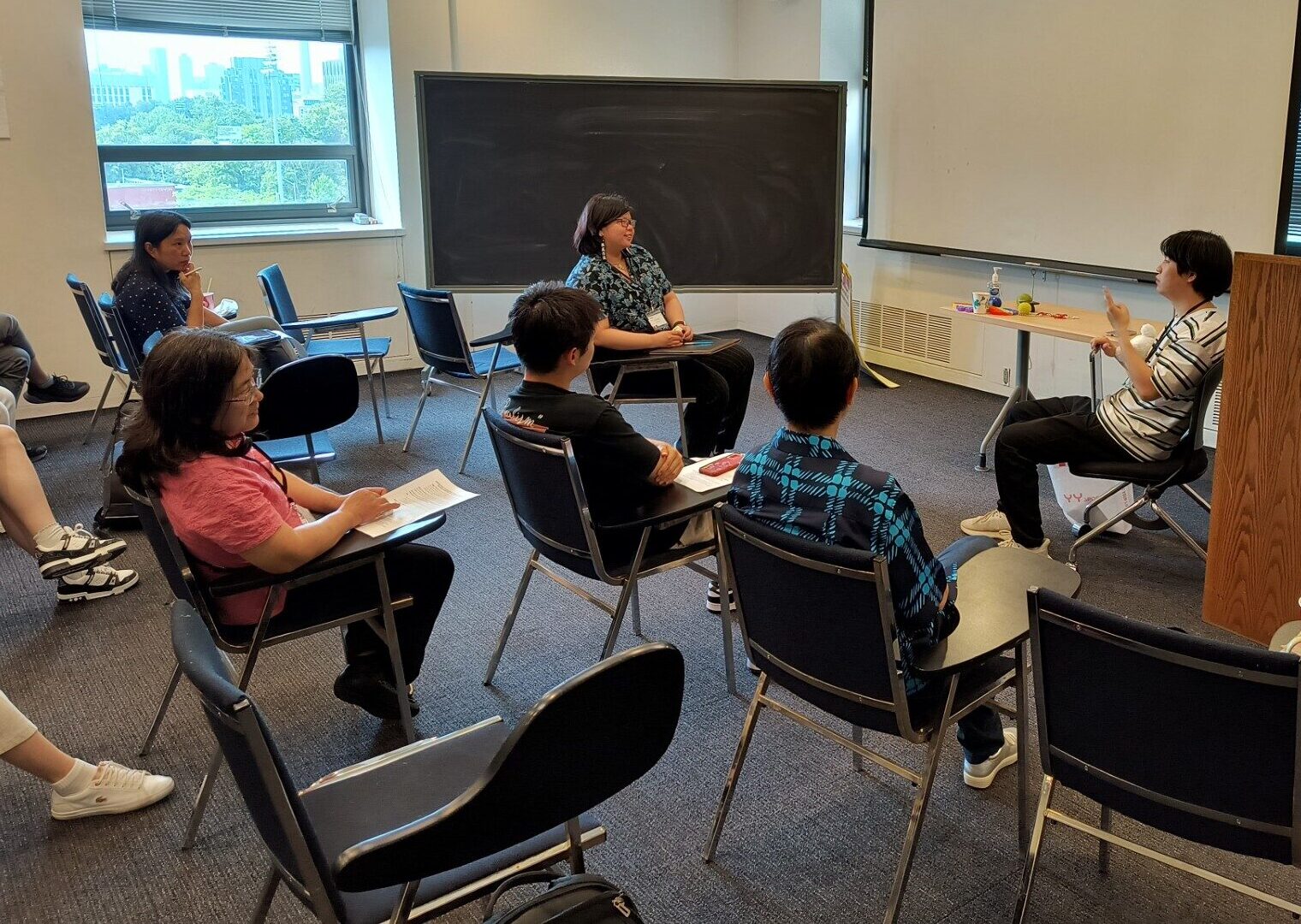

Using a community-based research approach, and inspired by the work of Associate Professor Izumi Sakamoto, Patricia Quan (top left) and colleagues held a one-day in-person storytelling forum at FIFSW with participants who lived in homestays or worked with students who lived in homestays.

International students pursuing elementary and secondary education in Canada can experience physical and mental health challenges in the unregulated homestay system due to adverse living conditions, discrimination and neglect, according to a new community report led by U of T social work graduates.

“It can be quite shocking for people who aren’t familiar with this system to hear what these children go through,” says Patricia Quan, a 2023 Master of Social Work graduate of the University of Toronto’s Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work and the principal investigator for the report, In Search of a Safe Harbor: An Exploration of the Experiences of K-12 International Students in Unregulated Homestays [PDF]. A former international student herself, Quan came to Canada on her own in Grade 9 and, like some of her co-authors (who are also former or current international students), lived in multiple homestays — an arrangement where international students who are minors live with host families.

Federal government statistics show that there were more than 70,400 international students enrolled in Kindergarten to Grade 12 (K-12) education in Canada in 2022. While there are no official statistics on how many of these children live in homestay settings, they’re known to be a popular option, says Quan.

The report is based on the stories of 19 participants who either lived in homestays or worked with students who lived in the homestays. Many of the student accounts, echoed by some of the workers, included descriptions of substandard meals, inadequate heating, a lack of privacy, cultural misunderstanding, and even racism and harassment.

Thanks in part to the mentorship of Associate Professor Izumi Sakamoto, whose research focuses on immigration, Quan and several other U of T graduates co-founded the SafeHarbor Project, which produced the In Search of Safe Harbor report in 2023 with funding from the Laidlaw Foundation. FIFSW PhD graduate Kedi Zhao , now an assistant professor at the University of Regina, is co-principal investigator for the report. The group’s goal is to create positive change in the homestay system.

“Our intent wasn’t to promote the idea that all students have negative experiences in homestays and all homestay providers are bad,” says Quan. “We wanted to expose the flaws in the larger system. Everyone that works or resides in the system — the homestay providers, the educators and professionals that support international students and the students themselves — is confused or poorly served.”

While there is a patchwork of best practices and guidelines for homestay providers, there is no single authority to enforce them, and no established mechanism for young students to express their concerns or report neglect.

“Language barriers, power imbalances and the students’ young ages all make them more vulnerable,” says Quan. “Even if they’re brave enough, resourceful enough and have good enough English to be able to speak up, the system isn’t equipped to address the problems.”

The report makes a number of recommendations, from formal licensing, ongoing monitoring and comprehensive training for homestay providers to more active involvement of international students’ parents. The report’s authors also suggested that community organizations mobilize and empower international students to effectively advocate for themselves.

International students’ families often hire agencies to arrange homestays along with study permits. Only occasionally are the homestay providers designated as the students’ legal representatives (i.e., custodians) who can make major decisions in areas such as healthcare and education in the students’ parents’ absence.

As a result, young students end up living in rooms within other families’ homes where the homestay providers provide shelter and often meals in exchange for a fee, but may otherwise deliver little to no care or guidance. “Students often feel overlooked or dismissed by their homestay families, which contributes to feelings of being invisible and unheard, and worsens their mental health struggles,” says Quan.

When students faced larger challenges in Canada, rather than address the issue by providing support and resources, the professionals in the sector often recommended that the international students simply “go home” due to the lack of understanding of students’ experience and the limited resources available for temporary residents.

“This default solution actively pushes the students out of Canada, perpetuating long-existing xenophobic sentiments,” says Quan. “It fails to take responsibility for the well-being of these young minors.”

Moving forward, the SafeHarbor Project will now be called Project Anchor , marking a shift from a narrower emphasis on fostering safety to nurturing a broader sense of belonging in homestays for international students in elementary and high school. The peer-led initiative will provide support groups for K-12 international students and continue to advocate for homestay system reform.

“The students who shared their stories with us have found it empowering, and so have I,” says Quan. “We’re using our lived experiences to start building the change that we want to see. It’s going to be a long journey, but I’m dedicated to keep going.”

By Megan Easton